The following is a list of questions that patients and caregivers often have about fibrolamellar carcinoma, its treatment, and getting involved or finding support. Click or tap the box containing the question (or the arrow next to the question) to view the answer.

Many of these answers are from our own research and experience, and do not necessarily represent proven scientific fact. Please note that the Fibrolamellar Cancer Foundation does not recommend doctors, endorse specific organizations, give medical advice or promote any specific forms of treatment. Instead, we provide website users with information to help them better understand FLC and current approaches to diagnosing, treating and researching the disease.

Functions of the liver

The liver is a large organ on the right side of the abdomen, above the stomach and below the lungs and diaphragm. It is protected by the rib cage. Adult livers generally weigh between 3 and 3 1/2 pounds and are reddish-brown in color. The liver is roughly triangular in shape and has two large sections: a larger right lobe and a smaller left lobe. The gallbladder, pancreas and intestines sit under the liver. The liver and these organs work together to digest, absorb, and process food.

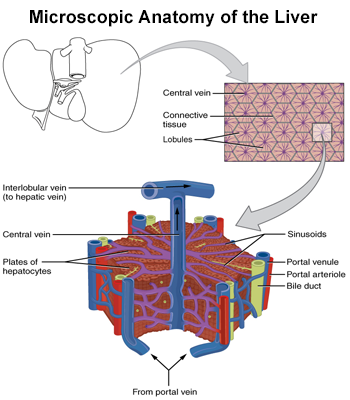

Unlike most organs, the liver has two major sources of blood. The portal vein brings in nutrient-rich blood from the gastrointestinal tract, and the hepatic artery carries oxygen-rich blood from the heart. The blood vessels branch into small capillaries, with each ending in a lobule.

The lobes of the liver are divided into roughly 100,000 liver lobules, where the vital functions of the liver are carried out. A typical lobule is 6 sided (hexagonal) and roughly 1mm in diameter. Each lobule consists of numerous cords of rectangular liver cells, called hepatocytes, that radiate from central veins toward the connective tissue that separates the different lobules. The plates of hepatocytes are one cell thick and separated by sinusoids, hepatic capillaries that give the hepatocytes direct access to the bloodstream.

The liver performs many essential functions. The liver is a vital component of the human digestive system, converting food into stored energy and chemicals necessary for life and growth. It removes waste products and foreign substances from the blood, regulates blood sugar levels, and creates many essential nutrients. It is impossible to live without the liver.

Overall, the liver performs over 500 vital functions in the human body, including:

- Eliminating the waste made after foods and other substances are broken down

- Producing bile, which carries away waste and breaks down fats in the small intestine during digestion

- Filtering blood coming from the digestive tract to remove toxins, byproducts, and other harmful substances

- Regulating blood clotting

- Producing albumin, the most common protein in blood serum that helps prevent fluids in the blood from leaking into other tissues

- Managing the conversion of fats from your diet and manufacturing triglycerides and cholesterol

- Converting carbohydrates into glycogen for energy storage and to make glucose as needed

- Regulating blood levels of amino acids, which form the building blocks of proteins

- Keeping the amount of nutrients in the blood supply at optimal levels

- Metabolizing bilirubin which is formed by the breakdown of hemoglobin and processing hemoglobin and storing its iron content for later use

- Converting poisonous ammonia to urea

- Storing certain vitamins and minerals, including vitamins A, D, E, K, and B12, for when they’re needed

- Helping to fight infection by making immune factors and removing bacteria from the bloodstream.

The liver is the only organ that can regenerate after it is damaged. If part of the liver is damaged or surgically removed, the remaining healthy liver can grow to compensate for the damaged or missing portion. Even if only 25 percent of the liver remains, regeneration can usually still happen.

FLC causes and impact

The exact mechanism driving FLC is not presently known, but researchers are working to learn the answer. In 2014, a unique fusion gene (called DNAJB1–PRKACA) that is common to most fibrolamellar tumors was discovered at Rockefeller University, and confirmed by other researchers. Because this fusion gene appears in the large majority of cases of the disease, it is likely to be very important to how FLC forms. Researchers have already shown that this mutated gene can cause liver cancer to form in mice. Researchers are still trying to figure out the exact role this gene fusion or chimera plays in the development of fibrolamellar, and the fusion gene has become a key target for new treatments for the disease.

Cancers are often described by the part of the body that they come from. However, because many areas of the body are comprised of different types of tissue, cancers are also classified by the type of cell that gave rise to the tumor. Carcinomas are a category of cancer that originate from epithelial cells. Epithelial cells line many tissues in the body, including the skin, respiratory system, blood vessels, digestive tract, and organs such as the liver. Hepatocytes, which comprise approximately 80% of the cells in the liver, are a type of epithelial cell.

For most patients with fibrolamellar, the diagnosis is made after a CT-scan or MRI of the abdomen is performed for either another reason, or after many months of general abdominal pain or fatigue. Imaging studies will often reveal a large liver mass. The diagnosis of FLC is then confirmed by obtaining a sample of the tumor by biopsy or surgery. The sample can then be examined under the microscope to identify the distinctive features associated with FLC, and tested for the DNAJB1–PRKACA fusion gene.

The following video from the Mayo Clinic Laboratories describes how FLC can be visually differentiated from other liver cancer types. It is a technical discussion, targeted mainly at medical professionals.

A cancer’s “stage” is a description of how much cancer is in the body. Fibrolamellar carcinoma is staged like other primary liver cancers, with cancer stages ranging from stage I through IV. In general, the lower the stage number, the less the cancer has grown or spread.

Liver cancer staging is based on the results of physical exams, imaging tests and biopsies or the examination of tissue removed during surgery. There are several different staging systems used for liver cancers like FLC. In the United States, the staging system most often used is the TNM system, developed by the American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC). This system is based on three primary factors:

- T (tumor) – a description of the number and size of the liver tumors

- N (node) – whether the cancer is present in a patient’s nearby lymph nodes

- M (metastasis) – if the cancer has spread to distant parts of the patient’s body.

Using this system, the following stages are determined:

- Stage I – A single primary tumor of any size has been found. The tumor has not grown into any blood vessels. In addition, the cancer has not spread to nearby lymph nodes or metastasized to distant sites. Sometimes this stage is divided into two subcategories:

- In stage IA, the single tumor is smaller than 2 cm

- In stage IB, the single tumor is larger than 2cm.

- Stage II – Either a single primary tumor of any size exists and has grown into liver blood vessels, or several small tumors are present. If several tumors are present, all are less than five centimeters in diameter. In addition, the cancer has not spread to nearby lymph nodes or distant sites.

- Stage III – Several tumors have been found and the cancer has neither spread into nearby lymph nodes, nor metastasized to distant sites. This stage has two subcategories:

- In stage IIIA – at least one of the tumors is larger than five centimeters.

- In stage IIIB – at least one tumor has grown into a branch of the portal vein or the hepatic vein – the major veins in the liver.

- Stage IV – Stage IV liver cancer includes two subcategories:

- In stage IVA – a single tumor or multiple tumors of any size have spread to nearby lymph nodes, but have not metastasized to distant sites.

- In stage IVB – a single tumor or multiple tumors of any size may or may not have spread to nearby lymph nodes, but have spread to another part of the body.

In addition to the TNM system, other liver cancer staging systems are also used, especially internationally. These other systems generally try to take into account the impact on the function of the liver as well. These systems include:

- The Barcelona-Clinic Liver Cancer (BCLC) system

- The Cancer of the Liver Italian Program (CLIP) system

- The Okuda system.

A prognosis is a forecast of the likely course of a disease in a patient. For patients with FLC, it is important to remember that every person is unique and their personal prognosis depends on many factors, including:

- the location of the tumor(s)

- if the cancer has metastasized (spread) to other parts of the body

- how much of the tumor was or can be removed by surgery.

Doctors estimate survival rates based on how people with FLC have done in the past. Because there are so few cases of FLC, these rates may not be very accurate. In addition, because treatments are continually changing and how specific patients respond to each treatment can be very different, the historical data cannot be used to predict exactly what will happen to an individual patient.

Previously reported survival rates for FLC range from 7 to 40 percent five years after diagnosis. We do know, however, that complete surgical removal of the tumor improves this survival rate. Combined with early detection, complete removal of the tumor can also decrease the rate of recurrence.

Patients whose tumors are not removed surgically have an average survival of 12 months, while those whose tumors were completely removed survived for an average of 9 years. Some fibrolamellar patients remain with no evidence of disease (NED) years, and even decades, after complete removal of the tumor and before any spread of disease.

Many new therapies are being used in patients today and some are yielding promising results, but we don’t yet have the data to prove their effectiveness.

If a patient is interested in getting information on their prognosis, it is important for them to talk to their doctors. Only a patient’s doctors can properly assess the individual’s prognosis and risks.

In order to spread, some cells from the primary original tumor must break off of the tumor, spread to another part of the body, and begin growing in the new location. FLC, like other types of cancer, can spread in two main ways:

- Through the blood. If cancer cells get into the bloodstream, they can be carried throughout the body. Anywhere along the way, the cancerous cells can initiate new tumors.

- Through the lymphatic system. If cancer cells make their way into nearby lymph nodes, they can be transported to other areas of the body.

The lungs, abdominal lymph nodes, and bone are the most common sites of metastatic FLC. Metastases to the brain are rare, but have been reported. However, no matter where metastatic tumors form, they are still the same type of cancer and will be treated as such.

Treatment questions

Click here for a listing of doctors – including surgeons, oncologists and radiologists – who we know have treated patients with FLC. If physicians in your area are not listed, you can also contact one of the comprehensive cancer centers in the United States for additional names.

Because of the rarity of FLC and the lack of systematic studies of the effectiveness of specific treatments, no proven “standard of care” aside from surgery exists for the disease. While the specifics of how individual treatments are used depends on a patient’s situation and stage of disease, the main therapies for fibrolamellar carcinoma include:

- Surgery: Surgery is typically used to remove as much of the FLC tumor(s) as possible. This surgery can involve either a resection, where part of the liver is taken out, or a transplant, where the whole liver is taken out and replaced with a donor liver.

- Systemic treatments, such as chemotherapy, targeted therapy and immunotherapy: When surgery is not possible or when the cancer has spread, systemic treatments that can reach all parts of the body are generally used to treat FLC. Because of the lack of statistical evidence on which treatments are the most effective, doctors often select particular treatments based on drugs approved for use with HCC or by using their best judgement on a case-by-case basis.

- Ablation or embolization therapy: Depending on where the FLC tumor is positioned, embolization (cutting off a tumor’s blood supply) or ablation therapy (using temperature to heat or burn a tumor) can also be used.

- External beam radiation therapy: In cases where metastases have spread beyond the liver, radiation therapy is sometimes used to manage the progression of specific tumors.

Please see the treatment options section of this website for more information about these treatments and procedures. Alternatively, click here for an overview of treatments for FLC on Medscape.com.

When dealing with a complex medical condition like FLC, getting a second opinion can help patients feel more confident about their diagnosis and treatment plans. Doctors’ opinions can differ, and they can offer different treatment options based on their backgrounds and experiences. Some doctors take a more conservative approach to treating their patients, while other doctors are more aggressive and utilize the newest tests and therapies. As a result, pursuing a second opinion is a common practice for cancer patients.

There are many reasons why FLC patients may seek another opinion during the course of their care, including:

- to confirm their diagnosis

- to be certain there are no remaining options for surgery when the cancer is still confined to the liver

- to investigate treatment alternatives

- to increase their personal confidence on how best to proceed with their care.

Here are some tips when seeking a second opinion:

- Look for medical providers who have experience in FLC. This web site contains listings of doctor with FLC experience (see the find a doctor section on our site). Directly contacting major medical centers or other patients can also be a helpful source for finding experienced providers.

- Many physicians may review your case and consult over the phone, which can greatly simplify the process.

- Check with insurance providers to understand your coverage for second opinions and if a new specialist accepts your insurance.

- Plan to bring all medical records, including copies of exams, tests, previous treatments and scans to any appointments.

- Be clear about why you are seeking a second opinion. Do you want confirmation of a treatment plan? Are you looking to identify new treatment options? Discuss this at your appointment.

- Carefully consider what you plan to do next. Does your care need to be transferred to receive the new treatment options? Are you comfortable with the logistics of getting care somewhere else? Can a new treatment plan be communicated to your original doctor? When choosing to transfer care to another doctor, make sure that the change is communicated to your current medical team.

Patients’ decisions about their health care are critically important. Taking the time to understand and consider all treatment options and approaches is an important part of being an effective advocate for your health.

A clinical trial is a research study designed to assess the safety and effectiveness of a particular treatment, and advance the understanding of the science behind the cancer or the treatment.

Currently there are several clinical trials open to patients with FLC. They can potentially participate in clinical trials that are specifically for FLC, trials that are open to FLC patients, or studies that are open to patients with any solid tumor.

For more information on the latest clinical trials, view our clinical trials page, or visit clinicaltrials.gov and search for fibrolamellar.

Patients should ask their doctors about the availability and appropriateness of different trials. Potential clinical trials can also be identified using clinicaltrials.gov and the clinical trials page of FCF’s website. Within the detailed descriptions of each trial, contacts are listed who can be called or emailed to ask about the trial and to see if it is an appropriate option.

In addition to what patients can find out about the trial itself, other factors are also important to consider when selecting a trial, including where a trial is located, how frequently patients have to report to the trial site, the nature of the treatment, and the costs of participation.

Several sites give a good overview of considerations and questions to ask when choosing a study. These include:

- The American Cancer Society (click here)

- Clinicaltrials.gov (click here).

The preliminary results of on-going clinical studies are usually not publicly available. For phase 2 or 3 trials, there may be published reports on the results from earlier phases. Occasionally, case studies of a trial treatment in a few patients may be published as well. If available, patients can sometimes find this information by performing an internet or literature search using the name of the drugs, the company and the condition treated.

However, as with all treatments, there is no way to predict what the results will be for a particular patient.

Genomic testing, also called molecular profiling or genomic profiling, looks for gene mutations within a tumor known to be associated with cancer. These are relatively new tests and they do not always provide patients with useful results. However, because there are many existing and emerging cancer treatments that target specific genomic mutations (see targeted therapies in the treatment options page), this testing can sometimes allow doctors to recommend treatments that target specific mutations within a patient’s cancer, or treatments that they feel could be effective based on the total tumor mutation burden (a measurement of the number of mutations carried by tumor cells).

Many major cancer centers, including Dana-Farber, Memorial Sloan Kettering, Mass General Hospital, University of Washington Medicine and others, can conduct a genomic analysis for patients. Some medical centers now routinely perform genomic tests for all cancer patients. In addition, several private companies, including Caris, Foundation Medicine, Guardant, Molecular Health, and Paradigm, perform their own versions of genomic testing.

Unlike many other cancers, FLC tumors often have relatively few tumor mutations other than the DNAJB1–PRKACA fusion gene. As a result, many FLC patients do not receive actionable results from these tests. Nevertheless, many FLC patients opt to pursue the testing, hoping to find and potentially benefit from new emerging targeted cancer treatments. If interested, patients should speak with their medical teams about the costs and benefits of genomic or molecular testing.

It is believed that most cases of FLC occur at random and not as a result of an inherited genetic trait. The fusion gene that is specific to FLC is a somatic mutation and not a germ-line mutation, an inherited genetic alteration that occur in sperm and eggs. Unlike germ-line mutations, which can be passed on to descendants, somatic mutations are not usually inherited. Somatic mutations are frequently caused by environmental factors, such as exposure to certain chemicals.

There is, however, a rare, inheritable genetic condition called the “Carney complex” that is characterized by spotty skin pigmentation and heart myxomas (a type of tumor). A few fibrolamellar carcinomas have been identified as part of the Carney complex. However, these fibrolamellar carcinomas have a mutation in the PRKAR1A gene instead of the DNAJB1-PRKACA fusion gene found in most fibrolamellar carcinomas.

Each patient’s doctor should determine which is the best scan to use and at what time intervals. Different scans yield different information and expose patients to varying amounts of radiation. CT scans do expose patients to additional radiation and in certain circumstances your doctor may choose to use a MRI, which is a form of imaging that uses magnetism and radio waves instead of radiation.

Studies have shown that there is a very small risk of developing a second cancer as a result of treatment with radiation or some types of chemotherapy. If a patient is concerned about these risks, it’s important for them to discuss their concerns with their treatment team. Doctors generally believe that the benefits of cancer treatments, including external beam radiation therapy, vastly outweigh these risks.

Doctors do not generally recommend specific diets or lifestyles for FLC patients. However, for most patients, it is important to eat a healthy diet and stay in good physical shape. The healthier a patient is entering treatment, the greater their chances of a smooth recovery. Patients should consult with their doctors about any restrictions in activities or diet that may be important to their health.

Getting involved or finding support

Support from others who have already dealt with FLC can be very helpful to both patients and caregivers. The following resources may help individuals make connections to get that support:

- Fibrolamellars of the World Unite! – FWU! is a closed Facebook group that includes only those touched by the disease. We encourage all newly diagnosed patients and their families to join by going to Facebook, typing in the group name and requesting to be included. An administrator for the group will get back to you quickly.

- FCF events – Since 2012, FCF has sponsored an annual patient and family gathering and other events designed to build bonds among the FLC patient and caregiver community. Please visit our events page for more information, or to sign up for a specific program.

Dealing with any type of cancer, not only a rare cancer like fibrolamellar carcinoma, can be a major financial burden on a patient or their family. The Fibrolamellar Cancer Foundation is a nonprofit organization and uses its financial resources to fund research into finding a cure for this horrible disease, so does not provide financial assistance to assist individual patients with the cost of their medical care.

However, there are many government-sponsored services, as well as programs provided by other nonprofit organizations, that can help patients cover or reduce their healthcare costs. The helpful resources page of our website includes a list of organizations that can provide many different types of help to cancer patients – including financial support, travel, and lodging assistance.

Visit the join the fight section of our website to learn about the many ways you can help advance our search for a cure for FLC.

The Fibrolamellar Cancer Foundation BioBank is a centralized repository of tumor tissue and blood samples contributed by fibrolamellar patients to advance research into the disease. The BioBank protects and preserves these samples and makes them available to qualified researchers interested in studying FLC. A single sample sent to our BioBank is routinely divided and shared among several different labs to support multiple research studies.

Please contact us at (203) 340-7805 or pcogswell@fibrofoundation.org if you are interested in donating tissue from an upcoming or past surgery. Our Repository Manager, Patty Cogswell, will discuss the process of donating tumor tissue with you and answer any questions you have.

For more information, please visit our donate tumor tissue page.

What is a healthcare advocate?

A healthcare advocate or patient navigator is a person who helps guide patients through the complexities of our healthcare system, and ensures that patients understand their illness and get the care and resources they need. A healthcare advocate can be a trusted family member or friend; an employee of a healthcare group or insurance company; a volunteer from an advocacy organization or hired professional.

This brief article from Johns Hopkins outlines the importance of having a health care advocate: The Power of a Health Care Advocate | Johns Hopkins Medicine.

Private advocates

Traditionally, family members or close friends have been the principal healthcare advocates for cancer patients. However, over the last few decades, private patient advocacy has also emerged – both volunteer-based and pay-for-service based. While hospitals generally only hire nurses or other medically-licensed professionals to serve as their in-house patient navigators, private advocates come from a variety of backgrounds. Many advocates enter the role because they, or a loved one, experienced a life-changing medical event and they want to share what they have learned. In many cases, these individuals have no prior medical experience or training.

Finding a private advocate

If patients are interested in private patient advocacy assistance, there are many sources of help. FibroFighters Foundation plays this role for some fibrolamellar patients. In addition, the Alliance of Professional Health Advocates (APHA) publishes the AdvoConnection searchable directory of healthcare advocates across the country. The National Association of Healthcare Advocacy (NAHAC) also publishes a national directory of providers, as well as regional directories of healthcare advocates through their regional groups.

Please note: The Fibrolamellar Cancer Foundation does not provide medical advice or recommend any specific organizations or services. We provide website users with information to help them better understand their health conditions and current approaches to the diagnosis and treatment of FLC. Always seek the advice of your physician or other qualified healthcare provider.