Overview

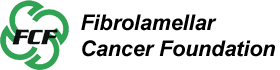

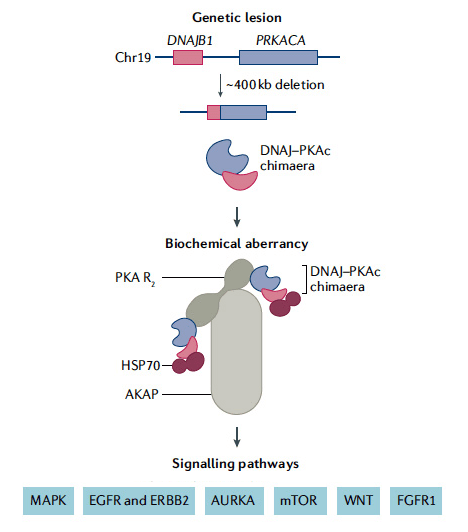

Fibrolamellar (fibro-la-mel-lar) carcinoma (FLC), also known as fibrolamellar hepatocellular carcinoma, is a rare liver cancer that primarily occurs in adolescents and young adults who have no history of liver disease. FLC was named in 1980 and recognized as clearly distinct from other types of liver tumors. The term “fibrolamellar” derives from the distinctive fibrous bands (lamellae) observed when tumor tissue is examined under a microscope (see figure below). In the early stages of the disease, affected patients often have no symptoms, so by the time the cancer is found, it may have already spread beyond the liver. FLC is different from the more common hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) in that it afflicts young people with normal liver function and no known risk factors.

Causes

Cancer generally starts when a normal cell in the body undergoes a mutation that allows it to divide uncontrollably. Descendants of that cell can expand in number and form a tumor. Mutations in several different genes may be required to create a malignant cancer capable of aggressive spread. Mutated genes that are implicated in a cancer’s occurrence are called “drivers.” Some driver mutations generate too much of a protein involved in cell growth and/or create an “activated” version of such a protein. Others may turn off genes that normally keep cells from dividing too much.

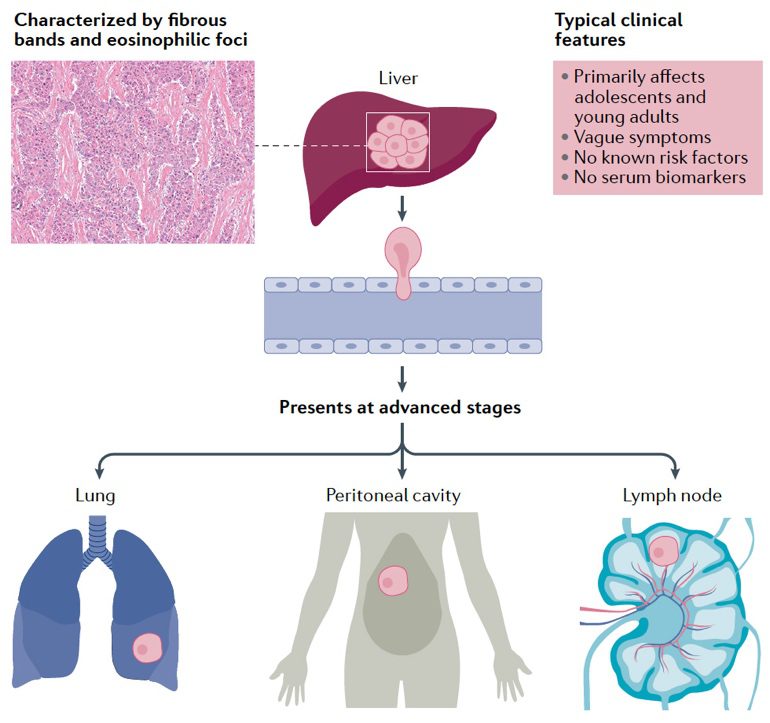

Importantly, all cases of FLC ever analyzed share a common driver – an enzyme called protein kinase A (PKA). PKA plays a critical role in the chemical signaling that controls several cell processes including growth and metabolism. The vast majority of FLC tumors contain an abnormal form of PKA that results from the fusion of the DNAJB1 and PRKACA genes (see figure). In 2014, in a research effort funded by FCF, this unique fusion gene was discovered at Rockefeller University, and confirmed by other researchers.

A fusion gene is formed when a chromosome (the part of a cell that contains the genes) breaks apart and reassembles in the wrong way. Both the DNAJB1 and PRKACA genes are located on the short arm of chromosome 19, and an in-frame fusion occurs due to a 400 kb deletion. This “driver” gene causes the production of a new fusion protein in the tumor. In the resulting fused or chimeric protein, a small portion of one end of PKA is replaced by a segment of an unrelated protein, named DNAJ (heat shock protein 40, HSP40). This “chimera,” which is referred to as DNAJ-PKAc, retains the essential chemical activity of PKA. However, something about the fusion changes the enzyme in a way that promotes fibrolamellar carcinoma.

Because this occurs in the large majority of cases of FLC, testing of the primary liver tumor for the DNAJB1–PRKACA fusion is now considered a confirmation that a patient has the disease. Scientists are currently trying to figure out how this fusion gene causes the development of the cancer, so they can identify new treatments.

Treatment

For FLC, surgery can be curative, especially when the disease has not spread beyond the liver. Consequently, current treatment of FLC emphasizes surgical removal of tumors, whenever possible. When the tumor cannot be removed surgically or when there is distant spread, many different systemic therapies are currently being used to treat the disease. However, no standard of care currently exists for FLC. Consequently, there remains a pressing need to identify proven, effective systemic therapies for the cancer. The Fibrolamellar Cancer Foundation prioritizes supporting research efforts that are most likely to lead to the development of more effective systemic therapies. (Please visit the treatment options page for a detailed description of FLC therapies and the research pages to learn about the research efforts FCF is supporting).

In this video segment, Dr. Allison O’Neill, a pediatric medical oncologist and member of FCF’s Medical & Scientific Advisory Board, discusses the key characteristics of FLC, as well as current and potential future treatment options for the disease.

Fibrolamellar Facts

Demographics

- Fibrolamellar carcinoma strikes males and females alike.

- The disease primarily affects adolescents and young adults, although cases in patients as young as 2 and as old as 74 are known.

Incidence

- FLC is an extremely rare disease and has been reported all over the world. Based on data from the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) program of the National Cancer Institute, the incidence rate of fibrolamellar carcinoma in the United States is 0.02 per 100,000 per year.

- The Foundation believes that the actual incidence of FLC in the U.S. may be undercounted, and is seeking to gather improved data to confirm the incidence rate of the disease.

Diagnosis

- Initial diagnosis of FLC generally comes from symptoms arising from advanced disease.

- Patients with fibrolamellar carcinoma often have non-specific symptoms or no symptoms at all. When symptoms develop, they are most commonly the following:

- abdominal pain

- weight loss

- malaise – a general feeling of being unwell.

- Fibrolamellar carcinoma was named for its distinct macroscopic and microscopic appearance. It’s features include sheets of tumor cells that are separated by fibrous collagen. This results in a characteristic “lamellar” pattern (see the image below). Fibrolamellar was first identified in the 1950’s and the disease was named by John Craig, MD.

Risk factors

- Risk factors for fibrolamellar are currently unidentified.

- Multiple factors, including genetic and environmental ones, are likely to play a role in the disorder’s development.

Genomics

- In 2014, a chimeric transcript (also called a fusion gene) was discovered that is common to the vast majority of FLC tumors.

- Because of this, the resulting DNAJB1-PRACA fusion protein is believed to be a major driver of this tumor and is a key diagnostic and treatment target.

- Aside from the fusion gene, FLC tumors typically harbor a low number of other mutations, very few of which are seen in multiple patients.

- This fusion gene is a somatic alteration, acquired by the cancerous cells at some point during their life. That means that the genetic mutation in the cancer cells is not present in a patient’s normal liver cells.

- Somatic mutations occur from damage to genes in an individual cell during a person’s life and are often caused by carcinogens or other environmental factors. Unlike a germline mutation, somatic mutations are not inheritable, and cannot be passed from a parent to a child.

Differences between FLC and HCC

- Fibrolamellar carcinoma differs from the more common hepatocellular carcinoma in several important aspects including:

- The presence of the DNAJB1-PRACA fusion gene which is unique to FLC

- Most patients with fibrolamellar do not have underlying cirrhosis or chronic disease of the liver, unlike many HCC patients

- Hepatitis B infection is very uncommon in patients with fibrolamellar, affecting less than 10% to 20% of all cases; hepatitis C infections are rarely associated with FLC

- Serum levels of alpha-fetoprotein (AFP) are usually not elevated in patients with fibrolamellar, whereas AFP levels are an important marker in HCC.

Additional definitions and descriptions of fibrolamellar can be found at: Medscape and RareDiseases.com.

Photograph in header is Eliane Wauthier of the UNC Chapel Hill laboratory of Dr. Lola Reid. Fluid in containers is the first fibrolamellar tumor line started with ascites from FCF founder Tucker Davis.

Please note: The Fibrolamellar Cancer Foundation does not provide medical advice or recommend any specific organizations or services. We provide website users with information to help them better understand their health conditions and current approaches to the diagnosis and treatment of FLC. Always seek the advice of your physician or other qualified healthcare provider.